Stuff that I've learned that I think is worth knowing or remembering or writing down or something

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Think Differently: Stop Working On The Proof

Always challenge assumptions and be prepared to think differently. (Or Think Different if you're an Apple aficionado. It's a good practice. And it takes practice.

Big Ideas I: The World Isn't Going to Hell

When I was a student here in Oxford in the 1970s,the future of the world was bleak. The population explosion was unstoppable. Global famine was inevitable. A cancer epidemic caused by chemicals in the environment was going to shorten our lives.The acid rain was falling on the forests. The desert was advancing by a mile or two a year. The oil was running out. And a nuclear winter would finish us off.I lived back then. I remember these dire predictions. And because all these claims were supported by large amounts of data and backed by respected academics, they seemed credible. Our doom seemed inevitable. And to top it off, the war in Vietnam was ramping up. A lot of us felt hopeless and helpless.

In 1968 Paul Ehrlich published "The Population Bomb." Ehrlich's thesis: resources are finite. Population is growing exponentially. Many people were already starving, and with growth, more and more would starve. Sooner or later (sooner, Ehrlich said) we would run out of food. Early editions said this:

The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.

Cover via AmazonIn 1972 a think tank called "The Club Of Rome" published a report called "Limits to Growth." Wikipedia describes the Club of Rome as a group of " current and former Heads of State, UN bureaucrats, high-level politicians and government officials, diplomats, scientists, economists, and business leaders from around the globe.[1] Using computer models developed at MIT and data on available resources to support their claims, the authors argued that the world was rapidly running out of resources, and with population growing exponentially, predicted that population would overshoot world's ability to sustain its population. According to the models, The inevitable result would be mass starvation, chaos, war, and Other Bad Things.

Cover via AmazonIn 1972 a think tank called "The Club Of Rome" published a report called "Limits to Growth." Wikipedia describes the Club of Rome as a group of " current and former Heads of State, UN bureaucrats, high-level politicians and government officials, diplomats, scientists, economists, and business leaders from around the globe.[1] Using computer models developed at MIT and data on available resources to support their claims, the authors argued that the world was rapidly running out of resources, and with population growing exponentially, predicted that population would overshoot world's ability to sustain its population. According to the models, The inevitable result would be mass starvation, chaos, war, and Other Bad Things.Around that time I read two books that not only changed my way of thinking about these predicted crises, but changed my way of thinking about all later projected doom scenarios . One book was "Utopia and Oblivion," by R. Buckminster Fuller. The other was "The Year 2000" by Herman Khan.

From Fuller's book I remember these key ideas:

- Prosperity is the best form of population control. In poor countries it is rational for parents to have as many children as possible: children are cheap to raise, and if one or several are even moderately successful, then they can support the parents in old age. In rich countries, it is rational for parents to have only a few children: children are expensive to raise, and there are other ways that aging parents can sustain themselves. So as countries become more wealthy, their reproduction rate drops.

- The world is becoming more prosperous. While it's awful that billions still live in poverty, it's also true that billions today live better than kings did a few hundred years ago.

- The history of the world is the story of doing "more and more with less and less." Fuller cites, among other trends, the change in the number of hours spent working for necessities (we get more and more food with less and less work), the amount of material required to build a building (we get bigger and better buildings with less and less material), the growth in food production (more and more food from less and less land.)

The bet doesn't mean anything. Julian Simon is like the guy who jumps off the Empire State Building and says how great things are going so far as he passes the 10th floor. I still think the price of those metals will go up eventually, but that's a minor point. The resource that worries me the most is the declining capacity of our planet to buffer itself against human impacts. Look at the new problems that have come up: the ozone hole, acid rain, global warming. It's true that we've kept up food production -- I underestimated how badly we'd keep on depleting our topsoil and ground water -- but I have no doubt that sometime in the next century food will be scarce enough that prices are really going to be high even in the United States.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Change Is One Decision Away--If You Practice

As I've written before: If I want to be a writer, I just have to be a writer. I don't have to do anything. If I want to do writing, I have to be a writer, and then start writing. If I want to have written something, then I have to be a writer, do the writing, and then keep at it until the piece is done.

The start of any change--to be something different, to do something different, or to have something different is just one decision away. Making decisions is not hard. If I'm not writing, and I want to write or to have written something (wanting is not the same as deciding) then the change will start when I decide to be a writer. Many times that's enough. I declare (once again) I am a writer. The decision results--almost magically--in me starting to write. And after a while I will have written something.

If deciding to "be a writer" doesn't do it, and I still want to have written something, then the next change is just one more decision away: to decide to write now. Not time in the future. But now.

The decision has to have a now in it because decisions have an expiration date. They are ephemeral. My decisions to be a writer and to write are effective only as long as I am on my way to writing (that is, walking up to my office, or pulling out a notebook,) or actually writing, or doing something while maintaining the deliberate intention to write about it later (doing it as a writer, rather than just doing it). Once I stop re-deciding or re-creating that decision, I go back to whatever state of being my environment seems to demand of me at the time--or if no demands then to just drifting.

Decisions produce change. A decision may start a visible change (a decision to act), or it may cause an invisible change that flows naturally into action (a decision to be). Absent decision things may happen but nothing really changes.

Making a decision is a skill. And keeping a decision in place is a skill. As with all other skills, if you don't deliberately practice you won't be very good. If you do practice, and do your practice deliberately, then after enough good practice, you will get good.

That's the goal of all practice: to be able to carry out an act without thinking about it. I've become strong at deciding to do my daily pages per The Artist's Way. Nearly every morning I decide "it's time to do my pages." The decision is effortless. The doing is nearly effortless. And I've got a stack of notebooks to prove it. What's in them? Who cares. The goal of doing pages is just to have done them. And I've done them. For more than three years.

But my other writing is sporadic. I think it's because I make the necessary decisions in a weak and undisciplined way, when I remember to do them at all. Here's what I do most often: not decide. Here's what I do second most often: I decide to write something (later), and later never comes. Here's what I think I should do:

- Remember to decide to be a writer

- Decide to be a writer

- Decide to write

- Write

- Keep those decisions fresh until the writing is done

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Most common words in English

If I can type in larger chunks then I can type faster.

So I should learn how to type the most common words, really, really fast.

Here are the 100 most common words.

How to type upside down.

Monday, August 15, 2011

Practice Starting!

This morning I realized (finally) that the solution to this problem was simple: I needed to practice sitting down. So I did. After my morning pages, I got up, went to the kitchen. I took a breath, and then headed back to my writing room, sat down, and wrote.

Then I got up and did it all over again.

Each time I did it, I did it a little differently, and each time I learned something.

The major lesson "learned" is something that I've known for a while: that if you want to get good at something, then you have to practice. I'm not good at sitting down to write, so I need to practice it.

More generally, I'm not good at starting. Once I start I can generally (not always) keep going, but starting is the hard part. So, the remedy is clear. I need to practice starting.

I'm also not great at finishing, but that's for another day. Right now my "deliberate practice" is starting.

To do that, I need to try to "deliberately start" whatever I do. I can practice starting lots of times, each day.

Who knows, I might even get good at it!

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Staying on Course

In a course on usability, my friend Jared Spool described what happens when you fly from New York to Boston. Most of the time, he said, the plane is off course. Still, you get there. What gets you there despite being off course most of the time is course correction. The pilot (or the autopilot) is constantly correcting errors. Head a little too far North and it points the plane a little further South. Perfection is impossible, so the correction will inevitably head the plane a little too far South. Fine. Correct it again. The wind blows harder than expected and you’re off course again. Correct it. You might get blown so far off course that you need to touch down and refuel. Get back up in the air and adjust your course once again. That’s how planes get from coast to coast. They correct, correct, correct and eventually they get there.

Life’s like that, too. You try to reach a goal and find yourself headed in the wrong direction. Maybe you’re not a little off course; maybe you’re way off course. It doesn’t matter. What will get you there is course correction.

It’s hard to course-correct effectively if you’re busy berating yourself for being off course. Self-criticism or self-abuse won’t get you back on course; it wastes time and energy. And it sucks.

Being hard on yourself won’t keep you from going off course again. When you’re flying a plane, going off course is part of flying. When you’ve living a life, going off course is part of living. You need to accept it, and adjust.

Sometimes the winds of fortune or errors in life navigation will push you way off course. So refuel. Do any necessary maintenance. Then get back flying again. But before you do, you might take a look around. Your unscheduled stop may turn out to be a pleasant surprise.

Hard to Make, Easy to Break

Good habits are hard to make, easy to break. I should know. I’m back in recovery again after having built, and then broken some really good habits. If I examine them, maybe I will learn something and be able to keep things going the next time.

And this post is further proof of how hard it can be to repair a broken habit. I started writing it on 7/26. The stuff that’s highlighted like this was written on 8/11 when I finally got the goddamn thing off my desk. But in the course of it I think I learned something. I hope I did.

So with that in mind, let’s proceed first to the data then the examination.

What Happened

In May I decided I was going to write. I was going to do it regularly and diligently. I started writing, and as I wrote I found good tools and configured them so my writing was easier and smoother. And I made a resolution: if I opened a web page with something useful, I would not close the page unless I’d written about it. I worked diligently on my other writing projects. And the results showed it.

| TWR | RSILT | WPFW | BWAS* | Other | Total | |

| May | 5 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| June | 8 | 35 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| July | 13 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 22 |

| Total | 26 | 47 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 88 |

This does not include daily pages, which are a well established habit for me, and it does not include my first ever stage play, started in June and finished in July.

And this does not count August which has been pretty much been a washout up to now.

To read the stats: my blogfest in May started near the end of the month, so those first 17 posts have to be extrapolated to the whole month. June was a rockin’ month. I was in a pretty steady state, with continuing improvements. And in July the roof caved in. Why? And what can I learn?

What happened in July?

The obvious and wrong answer was my computer problems. I feel like I have been fighting it all month. But that’s not true. It crashed the weekend I went down to Boston: that was July 10th. It’s only been two weeks that I’ve been fighting it. It just seems like forever.

Then I thought it might be Evernote. Once I started using Evernote I just clipped interesting web pages instead of blogging about them. Turns out this is half the story. I blogged about Evernote on July 6th. My Evernote notebooks show that I started clipping on July 3rd – and I started clipping articles about Social Media. Ahh!

So another answer: At the start of July Mira and I decided to work on a blog. That sent me into another round of process improvements—including Evernote. I let Evernote be a proxy for blogging what I learned about. Then the computer crashed. And things got worse from there.

And the last answer: I just lost momentum, and did not know how to gain it back. And here’s the proof. I started this particular post on 7/26 (or before—that’s the date of the last draft before I picked it up on 8/11)

Now what do I do?

Well, this is a first step [I wrote in my original draft]. I’m writing stuff in the blog. But it’s not enough. I’ve gotten out of some really good habits, and into some bad ones. Just getting myself to write this post was a real struggle. I kept wandering off, surfing web pages and NOT WRITING!

So the answer to this seems to be: put the discipline back into your life.

Really?

That was my remedy on 7/26. “Put discipline back in your life.” And where did it get me? Nowhere. Why? Because “Put discipline back in your life” is a slogan. It’s not a behavior.

And worse, I’ve got bad Beliefs. “I’ve lost control.” “I don’t know what to do.” “I can’t handle it.” All that old shit.

Well, I can handle it. And here’s how I’m going to do it.

My Daily Pages is a fully established, very reliable habit. When I started doing the Pages it was partly with the idea of making it a keystone or foundation (depending on your metaphor) for other good habits.

I got myself into the writing habit and when I lost it I did not have a reflexive way to recover. So I was unstable

What will stabilize me? My answer is good, tight management. I need to managed, or coached until the habit is set, and to intercede if I slip.

Right now I need management at a very granular level. A day is too long a time. The right level of granularity is: a Pomodoro at a time.

So here’s the current plan.

I will build on Pages. I will start each day with Pages, rather than doing them “some time during the day.” I will follow the Pages with Daily Planning. I will figure out some things that I am going to do—or at least attempt that day. Then start to work on the plan a Pomodoro at a time. Each time, write some notes. Coach yourself on a continuing basis.

Ellis cautions that to make changes it’s necessary to approach the problem both cognitively and behaviorally, and to reward the right result and penalize the wrong one. So: if no pages, I will take a cold shower. I hate cold showers. I have a strong incentive to avoid them. I will avoid them.

Will it work? Time will tell. Pages work. Building on Pages just might work.

I’ve got a new blog (Oh no! Not another!!!) Yes. It’s a personal one. To give myself that feedback and create a sense of history. It’s a personal blog. I may or may not make it public later on. We’ll see.

Today, under this new regime, I’ve done my pages, made my plan and made two posts in the personal blog. I’ve completed two Pomodoros of varying sizes.

This one will make three of each.

We’ll see what happens.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Not sucking at empathy

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Anyone can be anything

Then on to the next post, and the next, and the next. And if I do this (and other practices of writing) enough, I I'll get to my long term goal--maybe.

So I'm writing a lot. I've got five blogs going; I've just finished my first play; I've got some other writing projects in mind. My plan is to produce a few posts a week on each of the blogs. If I keep that up--or even amp it up beyond that--I might reach my long-term goal. Or I might die trying, which is not so bad, either.

At least you'll have fun.

Related articles

- How will you close in on your 10,000 hours today? (lisarivero.com)

- The 10,000 Hour Rule (bellwort.wordpress.com)

- What Malcolm Sees (lisarivero.com)

Friday, July 8, 2011

Do the Work: How to misery-proof yourself

I'm not miserable any more, but there certainly were times in my life when I was. And I've still got some scar tissue that needs healing, and a few raw spots that occasionally can be irritated. Books by him and his disciples have helped, as I have blogged, so I came back for more.

You'll have to buy the book to get full value. In fact, as he makes clear, you'll have to buy the book, read the book, and DO THE WORK to get full value. Insights can be useful, he points out, but in the end you've got to DO THE WORK. To make the point he devotes three chapters to this idea, and its variations.

He makes a good argument for his entire approach in the chapter titled "Can Scientific Thinking Remove your Emotional Misery." I'll retitle it: "Can Scientific Thinking Help You Do Lots of Stuff Better." Of course, his answer is yes, and so is mine. You can get some of the argument in this paper.

He says:

"Science is not merely the use of logic and facts to verify or falsify a theory. More important, it consists of continually revising and changing theories and trying to replace them with more valid ideas and more useful guesses. It is flexible rather than rigid, open-minded instead of dogmatic. It strives for a greater truth and not for absolute and perfect truth (with a capital T!).Later he makes what I am taking as the signature insight in my life: the importance of work and practice in any change.

The principles of RET [note: the B came later] outlined in this book uniquely hold that anti-scientific, irrational thinking is a main cause of emotional disturbance and that if RET persuades you to be an efficient scientist, you will know how to stubbornly refuse to make yourself miserable about practically anything. Yes, anything!

To challenge your misery, try science. Give it a real chance. Work at thinking rationally, stiicking to reality, checking your hypotheses about yourself, about other people, and about the world. Check them against the best observations and facts that you can find. Stop being a Pollyana. GIve up pie-in-the-sky. Uproot your easy-to-come-by wishful thinking. Ruthlessly rip up your childish prayers.

No matter how clearly you see...you will rarely improve except through work and practice--yes, considerable work and practice--to actively change your disturbance-creating Beliefs and vigorously (and often uncomfortably) act against them.

...to change your ideas [and behavior], you had better persistently work at doing so--since you are born and reared to think crookedly and to unconsciously slip...I like his emphasis on practice. And I really like his "shame challenging exercise." Ellis definition of "shame" is broad--it goes beyond the feeling we have when we do or think something that we would like to keep hidden and includes the feeling we would have if we did something silly, or unconventional, or even uncomfortable: like dancing in public, wearing odd clothing, talking to strangers, being laughed at by others.

Ellis says: when you've got such a concern, it's because you fear the consequences, which are generally imagined, and usually highly exaggerated. If you talk to a stranger they might turn away; they might say something nasty; they probably would not call the police; and they almost certainly would not beat you up--assuming that what you have said is unconventional and not insulting or provocative. So, he says: go out and do it.

He's used this himself, he tells us. As a young man he was uncomfortable speaking in public and afraid to talk to women to whom he had not been introduced. So he challenged the felling and gave speeches until he was not only comfortable, and he attempted to start conversations with over a hundred women in a one month period until he was entirely comfortable.

Watch out! I'm going to try that one. If you're ashamed of being seen in the company of a fool you probably don't want to be around when I do it.

Related articles

- 12 Irrational Beliefs (wpfw.blogspot.com)

- I've Changed My Story and I'm Sticking To It! (dawenings.wordpress.com)

Friday, July 1, 2011

Why self-discipline (sucking it up) sucks

I’ve realized that self-discipline, so-called, is a lousy technique for personal change, for me certainly. Now I know why, and based on this analysis I believe it sucks for everyone. I can use ABC+D to get a better result. So can you. Here’s why, and how.

According to the ABC theory of Rational Emotional Behavioral Therapy (REBT), discussed in this post, when behavior (a Consequence (C) ) runs counter to a Goal you’re trying to achieve, it’s not by accident. There’s a reason: an Activating event (A) plus a Belief (B) has led to the undesirable Consequences (C). To handle it, according to the theory, to get an Effective result (E) you need to uncover the Belief, and then Dispute it (D). Then you get to do what you set out to do. E=ABC+D.

What if I don’t use ABC+D but instead try to use "self-discipline” to get some desired result? As I have tried many times. After all, that’s what everyone says. Suck it up! Well, sucking it up sucks.

There are two problems with the self-discipline approach. The first is that usually it doesn’t work. The number of failed self-disciplined diets, self-disciplined exercise programs, and on and on worldwide—is enormous and growing daily. That’s a good reason to drop self-discipline, but despite that, people kept telling me and others to do it; and I’ve kept telling myself to do it, and then telling myself that I sucked when I couldn’t do it.

The second problem is worse. Suppose I do “suck it up” and force myself to do whatever it is I’m trying to do. When I do that, what am I actually doing? Well if the undesired behavior is because of a Belief that I hold then “self-discipline” equals forcing myself to do something that goes against my belief! The fact that I have an opposite belief doesn’t matter. I’m bullying myself to breach my own integrity by acting against something (however self-disabling in its consequences) that I believe.

Self-discipline then becomes self-brutalizing.

Better to find, Dispute, and change the Belief than to breach integrity.

Example: I want to write a post called “Self-discipline sucks.” Kind of like this one. Only finished. Instead of writing it, I find myself editing the first part over and over. Then surfing the web. If I do that (and I did)—I have some Beliefs that support those Consequence. And I do.

One Belief that makes me over-edit is: “What I wrote isn’t very good—so I should fix it.” I dispute it by saying: “Yes, but you know that if you go back to edit it before you finish your first draft, it will be both not very good and not done. You’ll be better able to make it good after you’ve gotten all your ideas down.” I quickly agree (this actually happened) and go back to completing my draft.

Another is: “I can always make it better—so I should keep working on it.” Dispute: “Yes, you can make it better. You can always make it better. No matter how good anything is, it’s not perfect, and so by definition you can make it better. But the fact that you can make it better doesn’t mean you should work on it more.”

One Belief that supports surfing is “I need to do some more research.” I dispute it by saying: “you know what you want to say. Just say it. You can find citations later.”

So, if you see this post, you’ll know that this was successful.

I suppose I could have beaten myself into finishing it, and I have in the past. But the beatings have stopped, because morale has improved.

And now it’s time to push the button and….post.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Memorandum from the Prefrontal Cortex

To: All staff

From: Your Prefrontal Cortex

Date: 21 June 2011 : 8:41 AM

Subject: Management training and organizational direction.

This morning, prompted by David Eagleman’s book "Incognito” (which some of my staff and I read this weekend) and using some other ideas we have acquired about neurological function, my executive staff presented me with a very exciting idea. I think it’s a Big Idea. I’d like to share with you now, and I will provide you with more information as we develop the idea.

Now to explain the Big Idea.

As some of you know I and the Prefrontal Cortexes (PFCs) of other humans are widely considered to carry the out the executive functions of the brain. We PFCs make high level decisions, meddle occasionally, and don’t fiddle with the details. This is often due to incompetence rather than disinterest. Consider visual perception. PFCs can decide (as can a few others parts of the human brain) what the eyes are to look at. In some cases we are asked to help resolve ambiguous visual data. But when it comes to image processing--to taking the raw data, as it arrives from our retinas and other sense organs, and turning it into information that is useful to us and to the rest of the organism--well, there we are completely out of our depth. For that work we depend on teams of specialists in the primary and secondary visual cortex, in the superior colliculus, and in many other units of the brain. They, in turn depend on support staff, including millions upon millions of unheralded glial cells who do such a great job of keeping things together and running smoothly. (My thanks to all of you in my brain!)

Responsibly for executive function makes me metaphorically speaking, the CEO of this organization. This is one of several useful metaphors the Eagleman uses, and I will be writing about later. Following this metaphor, I have certain responsibilities. One of them is continuous learning and finding ways to improve organizational performance. Carrying out this responsibility led to the Eagleman book and this Big Idea.

Another of my duties as CEO is assessing organizational performance. Of course, we know that our performance is excellent relative to most human beings, but I now realize that we do that in spite of our management techniques, my own included. Most of them date from well before the stone age! Modern civilization and continuing education have given us better management techniques than the ones that we inherited form our hominid ancestors. But the fact is most of what I, and others in management have learned—beyond our caveman tricks—has been learned in a haphazard and accidental way rather than an organized and intentional way. Following this management metaphor: none of has an MBA; we’ve gotten where we’ve gotten through on-the-job training. Indeed often it’s just been on-the-job experience, and not even training. Effective yes, but not effective as I believe a more structured approach would be.

So I'd like to start by focusing attention on my management skills and those of our executive management team. I’d like to consider, and have us all think about how we might improve those skills. Here are some of my initial thoughts. These will be developed further as we develop and roll out this plan.

We can start by simply adopting this management metaphor more widely and more consistently. Metaphors are powerful tools for human brains. They can help us acquire new ways of thinking far faster than "classroom learning” can. This one has certainly helped me.

Another way we can improve is by introspection, using this metaphor as a guide. We can find places where there are "low hanging fruit” for management improvement. I believe there’s a lot of low hanging fruit around, and I intend to have us pick it.

Another is by explicit

management training. There are several parts to the management training syllabus that I'm beginning to have in mind, and which I will address in later memoranda.Another approach, which I particularly want to note for future consideration, is to find ways to get fast feedback through outside coaching, either from others, or in some mechanical way. Eagleman has a section in his book that describes how airplane spotters and chicken sexers are trained. (Yes, chicken sexers!) They are not and cannot be trained by teaching them a set of steps to follow because those who have demonstrably acquired these skills can’t explain how they do it. They just do it. Airplane spotters and chicken sexers, among others, are trained through fast feedback from experts. I think this is applicable my own training—and training for many others of us.

I am asking the executive team, and indeed any of you with management responsibilities, to start looking for opportunities to improve your management skills. You might think that there are limits that derive from our organizational structure, which dates from even earlier than our pre-stone-age management techniques. Indeed our organizational structure makes “stone age” look positively modern! But recent research indicates we can do quite a bit within the existing framework—if we work at it. Particularly we may be able to open new communication pathways between related functions and change some of the ways in which we delegate decision-making and other responsibilities, to mention just two.

So, I'd like each of you individually, and in your workgroups, to consider what this new direction might mean to you. I know it means change. And I know many of you (thankfully) are responsible for our organization’s homeostatic self-regulation. Operationally this means that your job function is to resist change. I thank you for your excellent service in the past, but ask you to reconsider your role with respect to these changes, and think how you might retain homeostatic control but not block progress.

I believe that a well thought out, well planned, widely understood, widely agreed on, and well executed change effort can take what is already a highly successful organization, and move us fairly quickly to levels of performance (and satisfaction) that I, and some others of us have only dreamed of. That’s what I am hoping to develop, deliver, and ultimately help manage.

This is not (and given the way we are organized it cannot be) a unilateral decision. I expect discussion and I hope that this memorandum will generate a lot of new, good ideas. We are an excellent team and I see potential for us to do a lot better--individually, as teams, and as an entire organization.

Let me close by reminding you of what (I hope) is well known to senior staff, but which I may have not made explicit in the past. We have an open door policy here. We are looking for new ideas. We are also very interested in exploring, not suppressing, dissent. If this plan heads in a direction that you don't like, or are concerned about, then metaphorically speaking, speak up. We’d like to hear about these opinions sooner rather than later. We may adjust plans based on your input. Or we may need to communicate more clearly so that those of you who don't see value in our changes can support them—or at least not oppose them. I can't promise that we will please everyone (indeed, given the diversity of our group, I can pretty much guarantee that some will be dissatisfied) but I can tell you that as much as neurally possible that I and executive staff will listen, will do our best to understand, and will attempt respond to every one of you intelligently and respectfully .

Because of the time I've spent writing this memo, I believed that I had cancelled this morning's executive staff meeting—until one of my staff reminded me that this memo has actually required considerable staff input. I agree, and thank all of you for your help. This is a much better document than I could have produced by myself. We’ll meet, as usual, tomorrow morning, to discuss these ideas, and others.

As you can tell, I'm very excited by this idea. The cynics among you will point out that I am very excited by almost any new idea. And I admit that this is true. But I believe that this idea is one that, like daily pages which I have sustained for more than three years, I will be able to sustain. Indeed my plan is to use daily pages, which has served the occasional function of my executive staff meeting, to help ensure that this process continues.

These proposed changes will be new for all of us, and I'd like continuous monitoring and feedback as we proceed. I know that all of you are busy with other responsibilities, but my staff and I consider this very important. Please do your best to prioritize accordingly and please pass the word to any who do not receive this memo directly.

I'd like to get feedback quickly and directly from those who are in feedback loops directly connected to the Prefrontal Cortex, and indirectly from those who are not. And unless there are extremely strong objections we will proceed immediately to implementation

I'm looking forward, as always, to working with you.

Regards,

“Mike”

Prefrontal Cortex

Monday, June 13, 2011

12 Irrational Beliefs

From Albert Ellis, a definition of irrationality, and the most common irrational beliefs, with arguments (D) against them.

According to Dr. Albert Ellis and REBT, an idea is irrational if:

- It distorts reality.

- It is illogical.

- It prevents you from reaching your goals.

- It leads to unhealthy emotions.

- It leads to self-defeating behavior.

The list of twelve irrational ideas is worth reading, here.

Rational ideas

I found the following definition of rational thought useful (from a site on stress management)

Stress Reduction Techniques

Whenever you experience stress, it would help a great deal to check in with your perception of the situation before allowing your stress level to build too greatly.

Rational or Irrational?Ask yourself five questions to determine if your thoughts are rational or irrational.

1) If I believe this thought to be true, will it help me remain safe and alive?

2) Is this thought objectively true, and upon what evidence can I form this opinion?

3) Is this thought producing feelings I want to have?

4) Is this thought helping me reach a chosen goal?

5) Is this thought likely to minimize conflict with others?

In the place where I originally came on this idea, “The Small Book” by Jack Trimpey, he adds: “An idea can fail on one or two criteria and still be fairly rational, because rational thought is..nonperfectionistic.”

So an idea that: helps you remain safe and alive, produces feelings you want to have, helps you toward your chosen goal and minimizes conflict with others can be viewed as rational, even if not objectively true.

Related articles

- Myths about Rationality (psychcentral.com)

Sunday, June 5, 2011

ABC+D: an Example

This morning, writing my pages, I felt tired. I didn’t want to continue. This happens frequently, and when it does, I almost always stop writing and do something else. Instead I decided to Do the Metawork and analyze what I did.

Goal: easy. My goal is to write.

Activating event: I’m tired.

Consequence: I don’t write.

Conclusion: I have counterproductive beliefs. They need to found, and disputed. What are my beliefs?

“I’m just too tired to write.” Dispute: “Can you sit in a chair? Can you move your fingers? Then you’re not too tired to write.” “OK, I can write. But….”

“If I write something when I am tired, it won’t be good.” Dispute: “If you don’t write it, you’ll definitely not produce anything good. If you write, you won’t know if it’s good or not until you write it. There’s a good chance that some part of what you write will be good.” “OK, it might be good. And it’s true, I won’t know until I do it. But…”

“If I write now, I won’t enjoy it.” Dispute: “You might not enjoy it. But what would make you feel better: writing something even when you are tired, or giving up and not writing at all.” “OK, OK, I’d rather face up to my tiredness, and write.”

So I wrote. A lot.

Do the Meta{,meta} Work

Following Albert Ellis’s ABCD model, Beliefs control Consequences—or at least strongly influence them, so it’s important to to understand what we believe and to Dispute failure-promoting Beliefs and replace them with success-promoting Beliefs.

People usually categorize beliefs this way: a belief is true (consistent with known facts and perceptions), false (contrary to facts and perceptions), indeterminate (the facts are not yet known), or undecidable (no facts can be found to confirm or disconfirm the belief).

Another, and better way to categorize beliefs is this: a Belief is productive if it leads to Consequences that get one closer to the Goal; counterproductive if it leads to Consequences that get one further away; ineffective if it leads to Consequences that don’t affect achieving the goal.

This true/false/indeterminate/undecideable categorization is based on “facts” which are also beliefs. And the productive/counter-productive/ineffective categorization means that a Belief could be Productive, yet false.

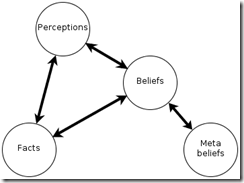

The relationship among these elements might look something like this:

Metabeliefs control Beliefs and can themselves be Productive if they permit Productive beliefs and Unproductive is they prohibit beliefs that can be productive.

Examples:

- I can only believe something if there is enough evidence.

- I can’t control what I believe.

- I can’t believe something that I don’t believe is true.

- I can’t easily change my beliefs.

- I can’t believe something that goes against my intuition.

Each of these metaBeliefs can be Disputed.

Saturday, June 4, 2011

ABC+D=?

My continued investigation into addiction has led me to Albert Ellis, one of the originators of cognitive/behavioral therapy. His particular therapy brand is called REBT, for Rational Emotional Behavioral Therapy.

Like most cognitive approaches, Ellis’s focuses on the links between perception, belief and behavior, and works to change the behavior by changing belief. ABC+D is an acronym describing his method.

The goal of REBT is helping people reach their goals more effectively—or at all. So REBT starts with defining goals. Then judge your actions this way: “Did that get me closer to my goal?” If so, then that action is good. If not, then bad. Regardless of the Consequence, you can use the ABC+D model to analyze what happened, and find better ways to reach the goal.

So let’s define terms.

A = Activating Event. An Activating Event is something noteworthy in pursuit of a goal. The event might block or delay reaching the goal. It might be a distraction. It might be a success.

B = Belief. A belief is something that you hold to be true. Activating Events do not result in behavior; according to Ellis’ model the event is interpreted, and action is prescribed according to beliefs. Change the belief, you change behavior.

C = Consequences. These are the results of some Activating Event. I might be a change in what you have been doing—or it might be no change.

All, right, this is nice and theoretical. Let’s take an example to see how it’s applied. Since I’m writing this post, and since I often have trouble finishing what I write (or do), I’ll use this as an example. My goal is to finish this blog post. Along the way there might be Activating Events that result in negative Consequence (I give up).

Of course sometimes the Consequence is that I succeed. We’ll look at that another time. It’s more useful (right now) to consider failure modes.

How do I fail? Often I I sit down to write then I find myself searching for something on the Web. Or I might find myself down in the kitchen looking in the refrigerator for something to eat. Whatever the case, I am not writing, so I am not reaching my goal. Something is getting in the way.

In this analysis we have one part of ABC—the Consequence. We have C, but we don’t have A and B. Now it’s time for detective some detective work. What’s the Activating Event? And what’s the Belief?

For me, a common Activating Event is this: I stop writing for a moment. Perhaps I review what I’ve read, and I decide I don’t like it. It might be missing something. It might be not well thought out. I might think that the argument is weak and has to be presented differently. Perhaps I don’t know what I might do next. The Activating Event is some disruption in my writing flow.

Fine. We have some examples of Activating Events. What Beliefs do I have that lead me to the undesirable Consequences? Doing a bit of introspection about writing failures, I dredge up these beliefs:

- I don’t know what to do next. This is a handy all-purpose Belief that leads me to “step back and think about things” or “take a break and see what comes to me.” These require some subordinate Beliefs:

- I have no way to figure out what to do next. If I did, then I’d be doing it.

- If I take a break, what to do next might come to me.

- I need to do some more research. Then I’ll know.

- This post isn’t going to be good—or good enough, so it’s a waste of time to work on it. I should work on something else.

- I really should be working on something that’s more important.

- I should be enjoying this—and I’m not.

Most of these beliefs lead to my undesired Consequence. One belief leads to a good Consequence. “I should be working on something more important” could lead me to work the more important project. It’s the others that are problems.

So now I’ve got a bad Consequence, an Activating Event, and a few representative Beliefs. That leads us to Ellis’s D step: Disputing.

Disputing is central to most forms of cognitive therapy. Activating events will happen—although sometimes we can do things to prevent them. For example if a person has a problem overeating and seeing a refrigerator full of favorite foods is a common Activating Event that leads to a binge—the probability of that Consequence can be lowered by leaving the refrigerator empty or filling it with foods that don’t lead to temptation. No Activating Event, no Consequence.

But most Activating Events can’t be prevented. Sometimes my writing flows and it’s all I can do to type as fast as I think. But sometimes I stop I might step back and wonder “How is this going?” That event might not be preventable. Or I just stop. There are no words coming to me. Here the leverage point is Belief. So let’s look at these Beliefs. But before we do this, let’s clarify my goal.

When I’m writing my goal is not to write something great, or necessarily even good. It’s just to write. My fundamental Belief is that if I practice enough, study my practice, and make adjustments, eventually I’ll get good.

With that in mind I can Dispute the Belief “I have no way to figure out what to do next,” by saying: “Yes, you do. You can just write whatever comes to mind. Eventually you’ll find something that makes sense. Or not. But at least you’ll be writing, which is the goal.”

Or I can Dispute “I’ll take a break and see what comes to mind,” by reminding myself: “If you take a break you’re likely to quit. Better to stay in your chair and keep going.”

Or I can Dispute “I really should be enjoying this, but I’m not,” with “It would be nice if you were enjoying this, but the writing process is not always enjoyable. What is enjoyable is finishing what you’ve started. So even though you are not enjoying this, keep going,”

Or I can Dispute “This post isn’t going to be good, or good enough,” with: your goal is to get a first draft done. Once you finish the draft you can criticize it and make it better.”

Or after enough frustration I get the belief Belief: “This is getting nowhere. I’m never going to be good writer.”

I can also Dispute it. “You may not ever be a good writer, but that’s not the goal. It’s to write at whatever level of quality you can achieve, and by practice get better. “

Examining, Disputing and changing these Beliefs might lead to a different Consequence: finishing the goddamn post. And if you are reading it, then indeed it has. As I’ve been writing this post, I’ve stopped from time to time and briefly reflected on what I’m doing. Some, but not all, of these troubling Beliefs have arisen. And I’ve Disputed them.

The result: as of this draft I’ve more than 1,260 words written. I haven’t gone off chasing the new. I’m pretty pleased with what I’ve written—and even more pleased that I’ve written.

Now I’ll answer the question that titled the article:

ABC+D = this post.

And more generally:

ABC+D = goals reached more often.

Related articles

- Rational Emotive Therapy Approach to Counseling (rumorsofglory.net): In this post, the author extends the ABCD acronym all the way to F.

- One Strong Belief: A Blog Post (sanjaysabarwal.com)

Saturday, May 28, 2011

I win!!

Here’s the pattern: sometimes B and I would get into a tiff. If I got my head out of my upset (some might say, if I got my head out of my ass) I’d resist reaching. “Why am I always the one who has to reach?” I’d ask myself. Myself would answer something unhelpful and more time would pass before things got cleaned up.

On a trip to Florida a couple of years ago, I came up with a great strategy for dealing with this, which we have now both adopted. I’ll tell it from my angle.

I realized that being the first one willing to reach was a strength, not a weakness. So I reached, and said, “I win!” Then I explained the new system that I was following. After a while B started to win, too. Now we both win, in lots of ways.

Handling addiction

Since characterizing myself in WPFW as a novelty addict, I’ve been reading a lot of recovery and recovery-related literature.

Most of the literature follows the 12 step process that I described in my earlier post, but last week I came on a different approach that made more sense to me, and lined up with a lot of other things that I have read.

So I’ll tell you the story of how I came to this latest great realization. I’ll start the story a few weeks ago when I came across a book by Steven Pressfield, called Do the Work. I knew Pressfield from having read his book The War of Art. I liked it, and tried to apply his ideas, but was not able to. Do the Work follows the same philosophy but is more action-oriented.

Here’s a summary of Do The Work from Pressfield’s blog.

Do The Work ... is an action guide that gets down and dirty in the trenches. Say you've got a book, a screenplay or a startup in your head but you're stuck or scared or just don't know how to begin, how to break through or how to finish. Do The Work takes you step-by-step from the project's inception to its ship date, hitting each predictable 'Resistance point' along the way and giving techniques and drills for overcoming each obstacle. There's even a section called 'Belly of the Beast' that goes into detail about dealing with the inevitable moment in any artistic or entrepreneurial venture when you hit the wall and just want to cry 'HELP!'

The kindle edition is free right now. I downloaded it from Amazon and read it in a night. It was inspiring, but still did not lead to the desired action. But it was a piece in the puzzle.

Pressfield’s idea is that when we embark on something positive, something he calls Resistance arises to stop us from doing our work. Pressfield describes resistance as: invisible, internal insidious, implacable, impersonal, universal—and part of ourselves.

Then last week I came across a book called Rational Recovery, by Jack Trimpey that seemed to supply a missing piece in the puzzle. Trimpey takes issue with the 12-step community (which he calls the “recovery industry”) and says, by contrast: recovery is easy. You just have to really want to do it, and know what’s going to try to stop you. He describes something very much like Pressfield’s Resistance that Trimpey calls “The Beast.”

Unlike Pressfield, who works principally (and maybe exclusively) from his own experience and mainly addresses artistic creation, Trimpey, a licensed social worker in California writes from a broader perspective that includes his own experience as a recovered alcoholic and from people suffering from drug addiction, alcoholism, and other similar problems, and mainly addresses addiction, not art.

Nontheless, they talk about the same thing. What Pressfield calls Resistance, Trimpey calls “The Beast.” Trimpey’s model is better developed, and more actionable than Pressfield’s, and is not just a metaphor but mapped to brain structure, as well. Pressfield provides inspiration; Trimpey provides depth

According to Trimpey, our better nature arises in our prefrontal cortex (PFC), the part of the brain that makes us uniquely human. The Beast arises in an older part of the brain, the midbrain, which concerns itself with pleasure and pain. The PFC is human; the midbrain is the brain of a beast.

The PFC can do the things that only humans can do: envision the pain and pleasure of the future; the midbrain knows only “now.” In alcoholism the PFC of a person seeking recovery may be able to assess the plusses and minuses of alcoholism and decide to quit, but the midbrain thinks only of the pleasures of alcohol and has no interest in or desire for quitting. The midbrain will do what is necessary, and at whatever cost, to drink the next drink.

It is as though there are two people there. One sincerely wants to stop drinking, and the other secretly plans to drink again. To recover addicts must recognize the “Addictive Voice” of the midbrain, recognize that they are in agreement with these secret plans. The one-day-at-a-time approach of a 12-step is then seen as a way to stop drinking today, but ensure that drinking tomorrow is possible. Only by deciding: “I will never drink again and I will never change my mind.” can the addict recover normalcy.

The 12-step process starts with an admission of defeat: “we recognized that we had no power over our addiction; that our lives had become unmanageable.” It is stronger than you, and you need your Higher Power, and the group to survive. Trimpey’s Rational Recovery starts with a recognition of Power. Hold out your hands and wiggle your fingers, Trimpey says. Now tell the part of you that wants booze to wiggle them. It can’t. Only you control what happens. You don’t need anyone else.

I don’t think my own problem is exactly mid-brain versus cerebral cortex, but after reading Trimpey’s book I realize that I am always ambivalent about my decisions to reform any of the habits that stand in the way of my meeting my goals. I want to write, every day, but I surf the web or watch TV instead of writing—or even do something somewhat worthwhile instead of writing. Why is that?

According to Trimpey, it’s because I have not make the necessary commitment: “I will never indulge in distractions while I have things to do that I have decided to do,” is hard to contemplate.

Hard, but not impossible. Reading these books has given me a much clearer understanding of what goes on in my own mind, and probably in others.

Tying this to The Time Paradox, which we studied in our last term at Acadia Senior College, Philip Zimbardo says that some people are “Present Hedonists” which means that they focus on the pleasures of the present rather than the past or the future. My own problem (or the one I am focused on right now) is a conflict between the hedonistic part of my brain that variety, and shiny new things and the part that wants me wants to follow certain self-chosen rules—like writing every day; like blogging all the S*&# that I learn each day—and doing it the day that I learn it; like playing guitar (not touched in 3 months) and so on.

So there’s a part of me (I’d like to call it me) that loves writing, guitar, keyboards, drawing, programming, and other creative acts. And there’s another part (the Hedonist, Resistance, or The Beast) that cares nothing about such higher objectives, and only about pleasure: watching TV shows that I don’t really care about; eating too much food; surfing the web for random shit (as opposed to researching with a purpose.)

When I was working it was worse there was a part of me that wanted to Do My Work (after all, I was getting paid a goodly sum to do it) and the Hedonist, Resistance and Beast that found that work to be—at best—not pleasureful, and at worst downright painful. (OK, pain is too strong, but you get the idea).

Trimpey also makes a nice distinction between someone who is addicted and someone who is “chemically dependent.” A chemically dependent person is one who uses alcohol, drugs, or some other substance to cope with life. An addict is one who uses the substance “against his better judgment.”

Trimpey points out that most people who fail to stop using their substance of choice do so because they don’t want to. Their problem may be bad judgment, but it’s not addiction.

So: I am a novelty addict because sometimes (not always) I chase the new “against my better judgment.” And the decision I think I need to make, for my personal recovery might be: “I will never succumb to hedonistic distractions against my better judgment again and I will never change my mind.”

Trimpey says that making such a commitment is part of a Big Plan: an event that ends addiction once and for all. If it’s going to be effective it’s not to be undertaken lightly. You have to be determined to face The Beast, or Resistance or The Hedonist and never negotiate. That’s really the key. It’s making the decision an absolute.

Inside, I can feel my own Beast rumbling as I move toward making my own Big Plan. Stay tuned.

Related articles

- 'Do The Work' by Steve Pressfield (thewayoftheweb.net)

- How To Get Serious About Your Creativity (twistimage.com)

Monday, April 18, 2011

Novelty addicts anonymous: getting into recovery

For years my problem has been diagnosed as mild ADD. Perhaps it is. But it's more helpful to me, right now, to look at it as a kind of addiction. I'll explain why, but first let me describe what I mean by addict and addiction.

We admitted that we were powerless over novelty addiction--that at least a part of our lives had become unmanageable.